Gastric Dilatation-Volvulus (GDV) is a rapidly progressive life-threatening condition of dogs that requires immediate medical attention. The condition is multifactorial but is commonly associated with rapid ingestion of large meals. The presence of food and gas causes the stomach to significantly dilate and expand, which may have several severe consequences, including:

- prevention of adequate blood return to the heart from the abdomen

- loss of blood flow to the lining of the stomach

- rupture of the stomach wall

- pressure on the diaphragm preventing the lungs from adequately expanding leading to decreased ability to maintain normal breathing

Additionally, the stomach can become dilated enough to rotate on itself, which is termed gastric volvulus. The rotation can lead to blockage in the blood supply to the spleen and the stomach. As gastric dilatation worsens and full body effects become prolonged, secondary complications may occur.

- Diminished respiration and cardiac output throughout the course of the disease leads to poor oxygen delivery to many tissues (hypoxia). This leads to cell death in the liver, kidneys, and other vital organs.

- Cardiac arrhythmias (abnormal heart beats) are commonly seen because of the hypoxia.

- The lining of the entire gastrointestinal tract is at risk of cell death and sloughing.

- Devitalization of the gastrointestinal tract can allow bacteria to access to the bloodstream and lead to bacteremia (bacteria in the blood) and sepsis.

Several studies have been published that have evaluated risk factors and causes for gastric dilatation and volvulus in dogs. This syndrome is not completely understood; however, it is known that there is an association in dogs that:

- have a deep chest (increased thoracic height to width ratio)

- are fed a single large meal once daily

- are older

- are related to other dogs that have had the condition

It has also been suggested that elevated feeding, dogs that have previously had a spleen removed, large or giant breed dogs, and stress may result in an increased incidence of this condition. A 2006 study also determined that dogs fed dry dog foods that list oils (e.g. sunflower oil, animal fat) among the first four label ingredients predispose a high risk dog to GDV.

Nearly all breeds of dogs have been reported to have had gastric dilatation with or without volvulus, but many of the commonly seen breeds are Great Danes, Weimaraners, St. Bernards, Irish setters, and Gordon setters.

Initial signs are often associated with abdominal pain. These can include but are not limited to:

- an anxious look or looking at the abdomen

- standing and stretching

- drooling

- distending abdomen

- retching without producing anything

As the disease progresses, your pet may begin to pant, have abdominal distension (bloated belly), or be weak and collapse and be recumbent. On physical examination, pets often have elevated heart and respiratory rates, have poor pulse quality, and have poor capillary refill times. Abdominal distension is commonly noted.

If your pet has exhibited any of the above clinical signs, they should be evaluated by your primary care veterinarian immediately. Surgery is indicated if the diagnosis of gastric dilatation volvulus has been established. Stabilization and surgery are best when performed early in the course of the disease since death (mortality) rates increase with the severity of disease. Your pet may be referred to an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon for treatment if this condition is diagnosed.

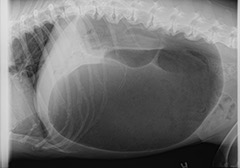

Most veterinarians will recommend initial blood work that includes a complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry, blood electrolytes, and a urinalysis. These allow for the determination of the nature of the metabolic disturbances that may be concurrently happening. It also allows your veterinarian to rule out certain diseases which may mimic the clinical signs of gastric dilatation. Additionally, abdominal x-rays are used to confirm a diagnosis (Figure 1) and an electrocardiogram (ECG) is used to evaluate the presence of cardiac arrhythmias which are commonly seen later in the disease course. Blood gas analysis is also commonly performed to evaluate the nature and severity of the respiratory compromise. Additional tests may be recommended by your veterinary surgeon.

Due to the hemodynamic instability that is encountered with these cases, most pets will require pre-operative stabilization such as intravenous fluids and oxygen therapy prior to general anesthesia. In cases where the gastric volvulus is suspected to have stretched and damaged splenic blood vessels, a blood transfusion may be indicated to address ongoing abdominal bleeding (hemorrhage). Gastric decompression often follows, which includes the passing of a tube down the esophagus into to stomach to release the air and fluid accumulation and can be frequently followed with lavage (flushing of water) into and out of the stomach to remove remaining food particles. In some cases, a needle or catheter may be placed into the stomach from outside the body to release air and aid in the passing of the tube. The time for general anesthesia and surgical stabilization will be determined by the stability of your pet and at the discretion of the veterinary surgeon.

Surgery involves full exploration of the abdomen and de-rotation of the stomach. Additionally, the viability of the stomach wall, the spleen, and all other organs will be determined. Removal of part of the stomach wall (partial gastrectomy) or the spleen (splenectomy) is performed if necessary. Once the stomach is returned to the normal position in the abdomen, it is permanently affixed to the abdominal wall (gastropexy). The purpose of this procedure is to prevent volvulus (rotation) if subsequent gastric dilitation occurs again.

Intraoperative and postoperative complications can include low blood pressure (hypotension), hemorrhage, surgical site infection, breakdown of suture (dehiscence), cardiac arrhythmia, shock and death. Most pets will be hospitalized and given supportive medication for several days after surgery. Vital parameters including cardiac electrical activity will be monitored. While many pets may develop a transient cardiac arrhythmia, most do not require additional treatment and should resolve with time. Severe postoperative complications can be associated with the effects of reperfusion injury or shock. Reperfusion injury is a sudden release of toxic metabolites from the stomach after de-rotation of the stomach and can lead to cardiac arrhythmias, acute kidney failure, and liver failure. Prolonged shock can result in organ dysfunction, coagulopathies, or death. Increased severity and time since the onset of the GDV is associated with increased complication and mortality rates. Mortality rates associated with gastric dilatation and volvulus have been reported to be approximately 15%. Factors that have been shown to increase mortality rate include patients:

- with clinical signs for more than 6 hours

- with cardiac arrhythmias prior to surgery

- requiring removal of a portion of the stomach due to loss of blood supply

- requiring removal of the spleen

Immediate postoperative care will include exercise restriction for a few weeks to allow the incisions to heal. Long term, dietary management will likely include multiple small meals (2-3) per day rather than a single large meal and continued monitoring for recurrence of clinical signs.

After this procedure, some pets may experience some degree of gastric dilatation without volvulus. This is typically encountered after a pet has ingested a very large meal. While the gastropexy will not prevent the stomach from expanding, it should serve to prevent the life-threatening gastric volvulus from occurring.

As a preventative measure, prophylactic gastropexy is currently being recommended by many veterinary surgeons for breeds at risk for development of the condition or in dogs that have relatives that have been related to others that have had this condition. Prophylactic gastropexy can often be done at the same time as sterilization surgeries (spay/neuter). Minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopic-assisted gastropexy, endoscopically assisted gastropexy and grid (limited approach) gastropexy are possible for prophylactic gastropexies (Figure 2).