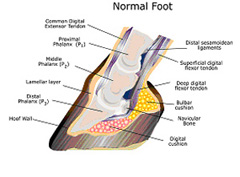

Laminitis (inflammation of the lamina of the hoof) is a common and potentially devastating foot problem that affects all members of the equine family: horses, ponies, donkeys, mules, and wild equids. The disease process involves a breakdown of the bond between the hoof wall and the distal phalanx, commonly called the coffin bone, pedal bone, or third phalanx (P3).

The distal phalanx/coffin bone in the horse is equivalent to the bone at the top of the human middle finger (Figure. 1a-drawing and 1b- radiograph). It is completely encased in the hoof. As with the human fingernail, the hoof wall is firmly attached to the coffin bone by a strong dermal-epidermal bond.

The hoof wall-coffin bone bond is the only thing that prevents the horse’s body weight (approximately 500 kg or 1100 lb) from forcing the coffin bone through the bottom of the sole of the hoof. This bond must be strong enough to withstand the forces sustained by the hoof at a gallop, yet dynamic enough to allow the hoof wall to grow.

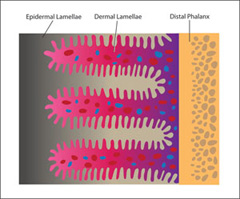

In order to maximize the strength of the hoof wall-coffin bone bond, this interface is connected by several hundred folds referred to as lamellae (Figure 2). The surface of each lamella is itself folded into many smaller secondary lamellae, which further increases the surface area and thus the strength of the hoof wall-coffin bone bond.

Because lamellae are formed by living cells with an extensive blood and nerve supply, the hoof wall-coffin bone bond is susceptible to a wide variety of systemic diseases that can contribute to the development of laminitis.

Primary Causes

- Grain overload

- Ingestion of lush grass

- Severe intestinal disease: Surgical colic or diarrhea

- Sepsis (circulating bacteria in the blood stream) due to, but not limited to:

- Pleuropneumonia

- Uterine infection due to retained placenta in post foaling mares

- Septic peritonitis (infection of the abdominal cavity).

- Exposure to black walnut shavings used for bedding

- Overweight bearing (ex: your horse steps on a nail on the left front limb & is unable to bear weight; if the problem in the left front limb is not resolved, the right forelimb is at a high risk for developing laminitis from bearing the majority of weight = contralateral limb laminitis)

Contributing Factors

- Excess circulating glucocorticoids; Equine Cushing’s Disease or corticosteroid administration

- Metabolic syndrome: typically associated with obesity

- Ingestion of ergot alkaloids, such as are found in endophyte-infested fescue grass or hay

- Inactivity (often coupled with obesity)

- Unaccustomed strenuous exercise

- Excessive concussion on the feet from exercise on a hard surface: “road founder”

- Stress: high-stress occupation or environment, long-distance transporting, hospitalization

- Poor hoof conformation or improper trimming or shoeing.

- History of laminitis: previous damage to the digital vasculature or the lamellar dermis

Signs of laminitis vary with the severity of the damage to the lamella and whether the laminitis episode is acute (hours or days old) or chronic (lasting more than a week). The most common sign that you would see is lameness ranging in severity from a minor head nod, to non-weight bearing and inability of the horse to stand up, having the appearance of walking on eggshells or saw horse stance An increase in digital pulse pressure in the arteries that supply the affected foot referred to as “bounding digital pulse” and/or the hoof wall feels warm/hot to the touch can also be a common finding as well, although not specific for laminitis. Laminitis most commonly occurs in the forelimbs and both forelimbs but can also occur in all four hooves, especially with circulating systemic disease.

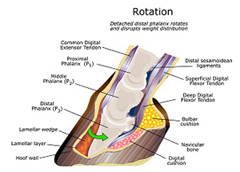

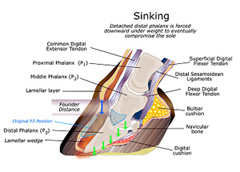

Whatever the cause, if the lamella is sufficiently compromised, the coffin bone can:

1) Rotate downward within the hoof capsule, forcing the tip of the bone down onto the dermis of the sole and compromising the vasculature (blood vessels) in that area (Figure 3/rotation) and/or

2) The entire boney column can drop or “sink” (Figure 4/Sinking) within the hoof capsule, causing severe pain and extensive vascular injury. Sinking can occur symmetrically or asymmetrically within the hoof capsule.

The hoof has an abundant supply of sensory nerve endings, so laminitis is a very painful condition. In fact, it is the extreme and unmanageable pain experienced by horses with severe laminitis that most prompts humane euthanasia in these cases. Other sequelae of severe laminitis that may worsen the prognosis for a good recovery include:

- Extensive destruction of the blood supply within the hoof

- Chronic bacterial infection within the hoof due to poor blood flow

- Prolapse of the tip of the coffin bone through the sole of the hoof.

- Bone destruction at the tip of the coffin bone from abnormal mechanical loading.

A diagnosis of laminitis is based on clinical signs of lameness, bounding digital pulses and radiographic findings. Radiographic changes also vary with the severity and chronicity of the primary cause. Radiographic changes range from thickening of the region between the hoof wall and the coffin bone, change in coffin bone density, to marked rotation or sinking of the coffin bone and, in chronic cases, destruction and resorption of the coffin bone.

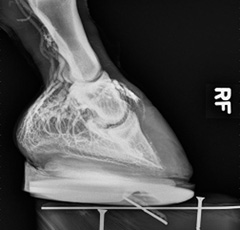

In addition to radiographs, contrast venography can be used to outline the individual blood vessels (white squiggly lines in Figure 5) within the hoof and can be a valuable addition to regular radiographs, because it reveals areas of reduced or absent blood vessels on the front of the hoof.

Typically once a horse develops laminitis and had recovered to a stable state, they will require special attention the rest of their life depending on how severe the overall clinical and radiographic signs are.

Your veterinarian may recommend the following types of long term care:

- Minimizing turnout, providing a deeply bedded stall or finding a turnout area that is of soft ground/sand with reduced grazing area

- Change in diet to a low carbohydrate/starch, minimizing grass intake (especially in the spring), soaking/steaming hay

- Corrective shoeing on a frequent schedule (every 3–5 weeks)

- Daily administration of anti-inflammatory medication (phenylbutazone (bute) or banamine) to help manage pain and make standing more comfortable

- Regular recheck radiographs (every 3 months to yearly based on your veterinarians recommendation)

As with treatment and aftercare, prognosis is directly related to the underlying primary cause, clinical signs and severity of diagnostic findings. What is critically important is that the primary cause is corrected and the progression of laminitis becomes stabilized (i.e., is not progressively worsening). In mild cases, some horses may be able to go back to their previous level of work. More commonly, it is a best case scenario that your horse may eventually become pasture sound. Often times and in severe cases, the clinical signs worsen and progression cannot be controlled. If uncontrolled, the severity of clinical signs worsen to where the horse may not be able to rise and either the tip of the coffin bone can penetrate through the bottom of the sole of the hoof and/or there can be complete detachment of the hoof from the underlying bone resulting in the horse “walking out of its hoof”. The most humane treatment option for the horse is euthanasia before the clinical signs gets even close to either of these points.

Potential complications following treatment for laminitis include, but is not limited to:

- If only one hoof was initially affected, the opposite limb may develop contralateral limb laminitis due to overweight bearing.

- Any other unaffected limb can develop laminitis, depending on the underlying primary cause

- Abnormal hoof growth – presence of rings, abnormal growth rate/pattern

- Repeated flare-ups of laminitis, meaning every few months to years.Clinical signs can become worse requiring repeated diagnostics, treatment and care as outlined above.

- Increased predilection for developing hoof abscesses, which will require veterinary care and treatment