Lameness refers to an abnormality of a horse’s gait or stance. It can be caused by pain, a mechanical problem, or a neurological condition. Lameness, most commonly results from pain in the musculoskeletal system (muscles, tendons, ligaments, bones, or joints) leading to abnormal movement at the walk, trot, or canter.

Lameness can range from being very mild (i.e. may not be easy to see but can be felt while riding the horse) to severe (the horse won’t bear any weight on the leg). With more subtle lameness issues you may notice a decrease in your horse’s performance or a change in their behavior or attitude even though you can’t see or feel an obvious lameness. Sometimes horses will “stand off” of a lame leg or point that leg more often than usual. Horses with chronic problems may develop compensatory gait abnormalities to deal with the primary problem. This may complicate the lameness evaluation and possibly its treatment. Therefore, it is important to have a lameness evaluated as soon as it is recognized.

If your horse is lame, it should be evaluated by your primary care veterinarian as soon as possible. In some cases, the examination may be simple; in others it may be more extensive, requiring nerve or joint blocks & diagnostic imaging to make a diagnosis. Your veterinarian may choose to do some or all of the following if your horse is lame:

- Take a thorough history; certain lameness issues are more common in different breeds or disciplines of activity

- Physical Exam:

- Palpation of the entire horse to check for any areas of heat, pain, or swelling

- Hoof testers – to see if there is a painful response to pressure on the feet (Figure 1)

- Lameness Exam: The horse is evaluated at various gaits to determine if lameness can be seen by your veterinarian. This may be done with an assistant trotting the horse in hand, on a lunge line, or occasionally while the horse is being ridden.

- Flexion Tests: These may be helpful if the lameness is subtle or there are no obvious signs of a problem (Figure 2); they involve bending or “flexing” a joint for up to 1-2 minutes. The horse is then immediately trotted off & evaluated for an increase in lameness. If a particular flexion test increases the lameness, your veterinarian may want to do further testing on that body part to determine if it is the cause of the lameness.

- Nerve or Joint Blocks (“Diagnostic Analgesia”): A local anesthetic is injected either around nerves or directly inside of a joint to desensitize specific structures on the horse’s limb (Figure 3). The horse is then evaluated again to watch for lameness. If the lameness improves after an area is desensitized, then the lameness is assumed to be coming from that location.

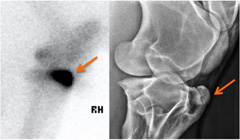

- Diagnostic Imaging: Once a specific part of the limb is isolated as the cause of the lameness, some type of imaging test is usually recommended. Depending on the body part involved your veterinarian may recommend radiographs, ultrasound, nuclear scintigraphy (aka “bone scan”, Figure 5), CT or MRI (Figure 4).

- Quantitative Assessment: The use of specially placed motion detectors on the limbs and trunk of the horse can aid in the detection of subtle gate asymmetries and responses to the aforementioned diagnostic tests.

Varies widely with cause of the lameness and the treatment given.