The intervertebral discs (the cushion in the space between the bones of the spine) have conditions and forces that can make them swell or rupture over time. This rupture leads to two types of damage to the spinal cord, compression and concussion. The extent of the damage and nerve cells loss is determined by:

- Type of force

- Degree of force applied to the spinal cord

- Length of time that the force was applied

Relatively minor spinal cord damage can lead to loss of coordination and a “drunken sailor” type of walk. Damage that is more significant leads to loss of walking or inability to move the legs voluntarily. Severe damage can lead to entire loss of pain sensation. This can carry a very poor prognosis for recovery depending on the duration that pain perception has been lost.

Chondrodystrophoid breed dogs (Dachshund, Pekinese, Beagle, Lhasa Apso, etc.) account for the vast majority of all disc ruptures, with the Dachshund accounting for 45-70% of all cases. In these dogs, average onset of clinical signs is between 3–6 years of age, although x-rays can show the presence of disc calcification by 2 years of age. Nonchondrodystrophoid dogs (Labrador Retrievers, German Shepherd Dogs, etc.) usually present between 5 and 12 years of age. Thoracolumbar (back region) discs account for 65% of all disc ruptures, while cervical (neck region) account for up to 18% of presenting cases.

Disc rupture presents with different degrees of pain; however, when nerve damage starts to develop and progress, it follows a predictable pattern:

- Back or neck pain, possibly refusing to walk around the room.

- “Drunken sailor” walk or wobbly in the hind end, hind feet will often cross as the pet steps.

- Complete loss of hind limb motor function. Usually at the same time, the pet loses the ability to urinate and the ability to void (empty) their bladder completely.

- Pain perception is lost, which is a sign of severe cord injury that can carry a guarded to poor prognosis.

Classification of disc ruptures is generally grouped into large regions. The following groupings are described:

- cervical vertebral 1–5 (C1–C5)

- cervical vertebrae 6 through thoracic vertebrae 2 (C6–T2)

- thoracic vertebrae 3 to lumbar vertebrae 3 (T3–L3)

- lumbar vertebrae 4 through the sacrum (L4–S3).

This grouping is called neurolocalization, which allows an ACVS board-certified surgeon to begin to plan which diagnostic tests and potential surgeries will be offered. Intervertebral disc rupture is generally thought to be a true surgical emergency and prognosis varies significantly with degree of function remaining when the pet is evaluated and surgically treated.

Most primary care veterinarians may suggest initial health screening, as well as any of the imaging techniques listed:

- Blood work: complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry, and a urinalysis

- X-rays of the spine or chest

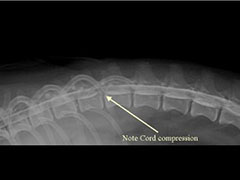

- Myelogram, which is an x-ray series where a needle injects dye around the spinal cord to highlight any compression (Figure 1)

- CT scan instead of or after the myelogram

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study in addition or instead of a CT scan

- Spinal tap at the same time as the imaging

Your veterinary surgeon will determine the most appropriate tests, which may vary.

Conservative treatment with cage rest, confinement, and pain medications is often only offered to patients that have recently begun their first episode and the neurologic deficits are mild. Further consultation with your veterinarian may result in a referral to a veterinary surgeon to fully explore your options.

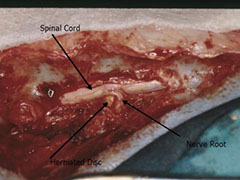

Multiple diverse surgical procedures and approaches exist, varying on the veterinary surgeon and the location of the disc. The choice of exactly which procedure to perform is made by the veterinary surgeon based on his or her experience and preferences. Surgical decompression of the spine by removal of the bone over the spinal canal is nearly always recommended (Figure 2).

Most pets are discharged 3–7 days after surgery. They are usually returned for recheck and removal of skin sutures or staples (if present). Pain can be well controlled with owner-administered medications.

Postoperative recovery following surgery may include:

- Bladder expression 3–4 times daily (if necessary)

- Physical rehabilitation for muscle strength and flexibility

- Exercise restriction to “bed rest” for at least 4 weeks

Lifestyle changes may include weight loss, switching to a body harness instead of neck lead, and minimizing jumping off furniture.

Postoperative complications can include:

- Myelogram could precipitate seizures in the first 24 hours after the procedure

- Incisional infection

- Many patients have another disc herniated later in life (~25% of recurrence)

- Continued wobbly walk or dragging hind toes when walking

Prognosis varies significantly with the degree of injury and the location of the injury. For dogs that still have perception of pain, surgical management can allow 90% of patients to regain their ability to use their limbs, although some may still have a residual wobbliness to their gait. Strict medical management for these cases may allow 60-80% of these patients to regain function. However, for pets with complete loss of pain perception, surgical management can allow 50-60% of them to regain their ability to use their limbs while strict medical management would allow <10% to regain function. Overall, the road to recovery after intervertebral disc disease can be a long one, usually spanning weeks to months. Recovery with medical management typically takes much longer compared to recovery after surgical management.

Pets that lose their ability to use their hindlimbs may also not be able to urinate well. Their ability to urinate on their own may potentially return if their neurologic condition improves. In the interim, owners will need to express their bladders several times a day so that they can void urine. These dogs are at a higher risk for chronic urinary tract infections and urine scald. Additionally, without motor function, patients cannot turn themselves, and may develop bed sores and wounds. Keeping these dogs on a soft, well padded area may help to minimize or eliminate these wounds. Patients may also develop tingly sensation (paresthesia) which may either resolve over time or be persistent and lead to self-trauma.