Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a relatively common condition affecting cartilage and bone in the joints of horses. It causes clinical signs in 5-25% of all cases. OCD is due to a derangement in endochondral ossification (bone formation during fetal development), and considered part of a larger umbrella called Developmental Orthopedic Disease. Therefore, while OCD does not have a predilection for breed or sex, it is widely considered a young horse condition. Malformed cartilage in OCD joints is irregular in thickness and weaker than in normal joints. This creates the cartilage and bone flaps we typically associate with OCD that either remain partially attached to the bone, or break off and float around the joint. These flaps and areas of abnormal cartilage and bone cause inflammation in the joint, and over time may lead to the development of arthritis. OCD is usually caused by a combination of several factors acting together, including:

- Rapid growth and large body size

- Nutrition: Diets very high in energy or have an imbalance in trace minerals (low copper diets)

- Genetics: Risk of OCD may be partially inherited

- Hormonal imbalances: Insulin and thyroid hormones

- Trauma and exercise: Trauma (including routine exercise) is often involved in the formation and loosening of the OCD flap

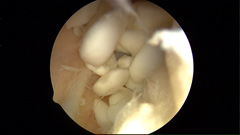

Signs and symptoms vary with age and use of the horse. In young horses not in work there can be no clinical signs. As a result, most Thoroughbreds undergo pre-sales films so OCD’s can be identified and removed before they cause a problem. It is also the reason radiographs are encouraged on a pre-purchase examination of a young horse. The most common sign in older horses or those in work is effusion (swelling) in the joint (Figure 1). Lameness varies with location and severity of the OCD; however, most horses are sound at a walk but display lameness at faster speeds or when workload increases. OCDs can occur in virtually all joints, but they occur most frequently in the hock, stifle and fetlock joints.

If an OCD lesion is suspected, your veterinarian will confirm this with radiographs. OCD is often bilateral and radiographs of the opposite joint should be taken, even if little or no swelling is present. Occasionally an OCD fragment is made entirely of cartilage (no bone) and thereforecan’t be seen radiographically. In these cases, only a defect in the bone is visible. Sometimes older horses are diagnosed with OCD incidentally without apparent clinical signs.

Horses with severe lameness and joint swelling probably have a more serious problem and should be examined on an emergency basis. If your horse has a swollen joint with lameness (plus or minus discharge), it should be examined by your primary care veterinarian to rule out more sinister conditions such as fracture or sepsis. Your veterinarian will probably want to do the following diagnostics:

- Physical Exam

- Lameness Exam

- Radiographs (Figure 2)

OCD is often bilateral and radiographs of the opposite joint should be taken, even if there is little or no swelling in that joint. Occasionally an OCD fragment is made entirely of cartilage (no bone) and so it can’t be seen on the radiograph; only a defect in the main bone may be seen in these cases. Sometimes older horses are diagnosed with OCD incidentally without apparent clinical signs.

Aftercare recommendations depend on the location and severity of the OCD, but typically involve a period of stall rest followed by progressive exercise. Full return to training may require several months. Postoperative bandaging will be required for some OCD locations and medication may be prescribed, including anti-inflammatory medications. A follow-up examination and suture removal may also be required. Specific recommendations on aftercare will be made by the veterinary surgeon for each case.

Prognosis for athletic function is good to excellent for most OCDs that are treated surgically. Some OCD locations, such as the shoulder, may have a reduced prognosis. In general, if the OCD lesion is not removed the prognosis for future soundness will be decreased. It is important to discuss the expected outcome, including appearance of the operated joint, with the veterinary surgeon during treatment selection.