The guttural pouch is a unique structure found in horses and only a few other species. It is an extension of the Eustachian tube, which is an air-filled canal that connects the throat to the middle ear. There are two guttural pouches (one on each side) that are located just below the ear in the throatlatch region (Figure 1). The function of these specialized air-filled sacs remains unknown but possible uses include pressure equalization across the eardrum, warming of inhaled air, a resonating chamber for vocalization, and aiding in the cooling of blood that flows to the brain during exercise.

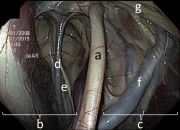

Each guttural pouch is divided into two compartments by the stylohyoid bone (Figure 2). There are a number of important nerves that run along the walls of the guttural pouch and control the muscles involved in swallowing, upper airway function, and facial expression. Additionally, several important blood vessels, namely the internal carotid artery, external carotid artery, and maxillary artery, all pass along the walls of the guttural pouch in order to provide blood supply to the brain and head.

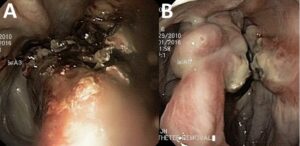

Guttural pouch mycosis is a fungal infection of one or both guttural pouches. Fungal plaques form within the guttural pouches, most commonly along the walls of the major blood vessels (internal carotid, external carotid, and maxillary arteries) (Figure 3). Over time, the fungus can erode through the wall of vessels, resulting in hemorrhage that can be life-threatening. If left untreated, a fatal bleed often ensues. The cause of guttural pouch mycosis is unknown, but the fungus Aspergillus is the most common type of fungus identified. There is no age, sex, breed, or geographical predisposition.

The most common clinical sign that horse owners will see is a moderate to severe nosebleed. This is due to the fungus eroding through the wall of one of the arteries located within the guttural pouch. The blood is usually bright red in appearance. Several smaller nose bleeds may precede a fatal episode, but any episode of blood coming from one or both nostrils should be considered an emergency and your primary care veterinarian contacted immediately for further evaluation.

The second most common clinical sign is dysphagia or difficulty eating and swallowing. This occurs if the fungus damages one or more of the nerves that control tongue movement and swallowing. Dysphagic horses may struggle to prehend food, be seen quidding or dropping feed, cough and have feed containing nasal discharge while eating, and pack feed in their cheeks because they are unable to properly swallow.

Other clinical signs less commonly observed with guttural pouch mycosis include the development of Horner’s syndrome (drooping eyelid, constricted pupil, sunken eye, and patchy sweating on the neck observed on only one side), white nasal discharge, abnormal head posture, and pain in the throatlatch region. Additionally, abnormal respiratory noise can occur due to damage to the nerves that innervate the muscles of the throat.

Endoscopy of the guttural pouch is the goal standard to diagnose guttural pouch mycosis. This involves passing an endoscope, which is a small flexible camera, up the nose and into the guttural pouches. Blood can often be seen coming from one or both guttural pouch openings if the horse is examined shortly after an episode of a nosebleed (Figure 4). Within the guttural pouches, fungal plaques, which appear as white, tan, and black membranes overlying one or more blood vessels, can be seen (Figure 3). The appearance of fungal plaques within the guttural pouch confirms the diagnosis of guttural pouch mycosis. The size of the fungal plaques can vary, but the size of the lesions bears no relationship to the severity of the disease.

Medical Treatment

Medical treatment for guttural pouch mycosis involves the infusion of topical antifungal agents into the affected guttural pouch with or without systemic antifungal medications. The response to topical treatment is generally slow (taking up to 5 months) and the success of such treatment varies greatly. There is also a substantial risk that a fatal bleed could occur during the course of treatment. Therefore, medical treatment is not usually recommended.

Surgical Treatment

There are several surgical options to treat horses with guttural pouch mycosis. Most treatments aim to occlude or block the affected artery to eliminate the risk of hemorrhage. Once the blood supply to the fungus has been removed via the occlusion of the artery, the fungal lesions usually regress without additional treatment (Figure 5). An ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon can help an owner determine what the best surgical options may be for their horse depending on what structures are affected by the fungus.

- Balloon catheter occlusion of the internal carotid artery. This technique places an inflatable balloon that is attached to a flexible catheter into the internal carotid artery via a small incision in the upper neck. Once the balloon has been correctly positioned within the internal carotid artery, the balloon is inflated, thus stopping blood flow through the artery. The end of the catheter is coiled and secured under the skin. The balloon and catheter are usually removed within 1–4 weeks after surgery.

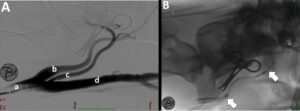

- Transarterial coil or plug embolization. This procedure places small coils or vascular plugs in the affected artery segments to stop the blood flow. The coils and plugs are designed to expand once appropriate placement is achieved within the artery. Rapid blood clot formation is achieved and blood flow is stopped. The procedure allows more precise placement of the coils or plugs compared to the balloon catheter technique, as the coils/plugs are placed under fluoroscopic guidance. Fluoroscopy is an imaging modality using X-rays that allows a surgeon to both map out the course of the arteries and directly visualize the correct placement of the coils/plugs in a particular artery in live time (Figure 6). This eliminates the concern that individual variability may exist between horses and ensures that the correct vessels are occluded. The specialized equipment needed to perform this technique makes the procedure less widely available.

The aftercare for horses following surgical treatment for guttural pouch mycosis varies greatly depending on what structures were affected by the fungus. In horses in which bleeding is the only pre-operative sign, aftercare is usually minimal. The fungal lesions usually regress over 30–180 days after the affected artery has been occluded, and additional antifungal treatments are not necessary. If a horse does not die from a significant nosebleed and surgery is performed as soon as possible, the horse usually has a good prognosis.

If signs of nerve dysfunction are present before surgery, then these horses may require additional aftercare or surgical procedures. Horses having difficulty eating may require intravenous nutrition or to be fed via a tube that is passed into their stomach. Horses with upper airway dysfunction may require additional surgery to treat the airway problem. Recovery of nerve function can be slow and may take up to 6–18 months, with some horses never fully recovering.