The long bones of dogs and cats are almost identical to the bones of the legs and arms of people. Dogs and cats can break these bones due to vehicular trauma, fights with other animals, and some sporting injuries, to name a few causes.

Limb anatomy:

| Front feet: | phalanges (toes; three bones in each toe) metacarpal bones (hand; four main bones) carpal bones (wrist) |

| Forearm: | radius and ulna |

| Upper arm: | humerus and scapula (shoulder blade) |

| Back feet: | phalanges (toes; same as front feet) metatarsal bones (foot; four main bones) tarsal bones (hock or ankle) |

| Lower leg: | tibia (shin bone) and fibula |

| Thigh: | femur |

| Pelvis: | ilium, acetabulum (hip socket), ischium |

| Joints: | carpus (wrist)—made up of small carpal bones and radius elbow—made up of radius, ulna and humerus shoulder—made up of humerus and scapula tarsus (ankle)—made up of small tarsal bones and tibia stifle (knee)—made up of tibia and femur hip—made up of femur and pelvis (acetabulum) |

A bone can break in many ways and we call these breaks “fractures.” To make it easier to plan for therapy, veterinary surgeons classify fractures into several categories.

- Incomplete: a fracture that is more like a bend in the bone; the bone may only be broken partway around the circumference of the bone; most commonly seen in young animals (Figure 1).

- Complete: the bone is broken through its full circumference and two or more bone fragments are created (Figure 2).

Complete fractures are further described based on the shape of the break.

- Transverse: the break is straight across the bone at a right angle to the length of the bone

- Oblique: the break is at a diagonal across the bone, creating two bone fragments with sharp points.

- Comminuted: the break is in three or more pieces of varying shapes (Figure 3).

A fracture that results in an open wound in the skin is called an open fracture; these can be created when the broken bone penetrates the skin (from the inside out) or when an object goes through the skin and breaks the bone. If there is no open wound near the fracture, it is called a closed fracture. Open fractures are considered more emergent than closed fractures because of the risks associated with infection.

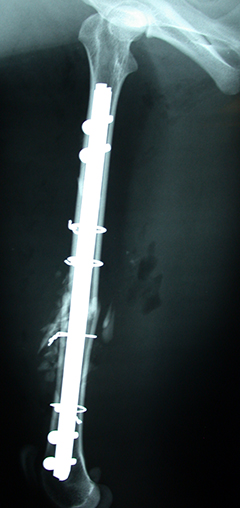

| Figure 1: An incomplete radial fracture in a dog. | Figure 2: Complete fractures of the right radius and ulna of an adult dog. | Figure 3: A comminuted tibial fracture of an adult dog. |

|

|

|

|

Typically, severe lameness is noted and the affected limb is obvious. Most pets with fractured limbs will hold up the affected limb. Some pets are able to bear some weight on the limb, depending on the location and nature of the break. Pets that have sustained major trauma, such as being struck by a motor vehicle or falling from a height, may have more than one broken limb, and may be unwilling or unable to walk. You may notice swelling, pain, or abnormal movement at the affected site.

When the fracture is secondary to trauma, it is very important to note that other systemic signs may be possible. Abdominal trauma can result in hemorrhage (bleeding) and ruptured organs (such as urinary bladder). Thoracic trauma can result in pulmonary contusions (bruising and hemorrhage within the lungs), hemorrhage around the lungs, and air around the lungs cause by a tear in the lung. All of these conditions can be very critical injuries and may delay the definitive treatment of the fracture.

Your primary care veterinarian or emergency veterinarian will assess your pet thoroughly, to evaluate for any other injuries to vital organs. Your veterinarian will likely recommend x-rays of the affected region. Often times pets need a pain medication or sedatives in order for x-rays to be obtained. Other tests that may be recommended initially include complete blood work, abdominal and thoracic (chest) radiographs, and possibly an abdominal ultrasound. Occasionally, a CT scan of your pets entire body (trauma CT) may be advised.

Initial Management

When a bone breaks, one of the first things that needs to happen is for the bone fragments to be immobilized so they cannot move. A fracture that is immobilized will hurt less and the sharp ends of the bone fragments will not cause further damage to the muscles, nerves and blood vessels surrounding the bone.

At home, before you are able to get to a veterinary clinic or hospital, you should confine your pet to a very small space. Ideally your pet is lying down in a box, crate or kennel, and movement is limited to only that necessary to go to the bathroom or maintain cleanliness. Seek veterinary care as soon as possible (at least call to receive instruction). A bone fracture is very painful and other dangerous medical conditions may have been created at the same time as the fracture. Do not give any medications or apply any therapy unless you receive clear guidance from your veterinarian.

Closed fractures are ideally treated within 2–4 days and open fractures are best treated with an initial procedure to clean the wound and bone within 8 hours of the injury. A final surgery for open fractures can be delayed for 24–48 hours.

Often the best way to temporarily immobilize a fracture prior to final treatment is to place the limb in a splint. To properly immobilize a bone, the joints above and below the affected bone must be prevented from moving. It is fairly easy to temporarily immobilize bones below the elbow and below the knee, but the upper arm and the thigh are more challenging to manage because the shoulder and hip are difficult to splint. For fractures affecting the upper arm or thigh, your veterinarian will likely recommend simply confining your pet to a small space while plans for definitive treatment are made. Splints and bandages, as well as confinement, are best managed at a veterinary facility.

Fracture Repair

When a bone is broken, it is unable to resist the normal physical forces that act on bones when a pet walks on a leg. Some of these normal forces are:

- bending (like the force used to break a pencil in half)

- torsion (a twisting force around the bone)

- compression (the force that gravity puts on us when we bear weight on our legs)

- traction (the pulling force applied to a small portion of bone by a muscle at its attachment on the bone)

The strength of normal, healthy bone resists these forces. A bone breaks when it is subjected to a force that is greater than its own strength. Once it is broken, it must be immobilized sufficiently to allow the bone to heal back together. This is where veterinary treatments, like those listed below, are used to ensure quality bone healing and good leg use.

External coaptation: a splint or cast; applied to the outside of the limb; good at resisting bending forces and fair at resisting torsion and compression forces.

External fixation: a surgically applied device that is attached to the bone with pins that thread into the bone, but come out through the skin. These pins are connected to a rigid bar with clamps to “splint” the bone on the outside. This method is very good at resisting bending, compression and torsion forces (Figure 4).

Internal fixation: surgically applied devices implanted inside the bone or on the surface of the bone. Various devices are available and offer different results against the various forces. These devices include bone plates, screws, nails, pins, and wires (Figures 5 and 6).

Several factors go into making up a final treatment plan for a fracture. Each factor has characteristics that support easy/rapid fracture healing and characteristics that result in slow/complicated fracture healing. We use this scale of information to come up with the best repair options for an individual pet. Your veterinarian may refer you to an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon for your pet’s fracture repair because of the experience and training involved in successful fracture fixation.

|

||||||||||||||||||

After all is considered, you may be faced with choices for fracture repair. Your veterinary surgeon will help you decide which option might be best for your home environment, time investment, and possible financial constraints. A splint or cast repair option is not necessarily the “easiest” or “cheapest”. Splints and bandages require frequent evaluations and changes and complications may result in a longer overall healing period, whereas some fixation methods improve the chance of successful outcomes without demanding post-operative care. Your active participation in this decision-making process will improve the overall outcome of your pet’s medical condition.

As a general rule, follow all instructions provided to you by your veterinary surgeon. Some of those instructions may include the following recommendations:

Bandage Care

If your pet has splint or cast for final fracture treatment or if a bandage was applied after surgery to help with pain and swelling, careful monitoring and maintenance is necessary for safe and effective bandage wear. Major problems can result from simple bandages. Please do not hesitate to call your veterinary surgeon if any problems are noted.

Monitor the bandage for slipping, soiling, or damage from chewing. If it changes position or becomes wet or loses its integrity, serious problems may occur with healing or new problems with pressure sores may develop. Please call your veterinarian if any changes in bandage position occur; the bandage may need to be replaced.

If the end of the bandage is open, check the two central toenails twice daily. They should be close together. If they are spreading apart, this indicates toe swelling, which can result in serious complications, and the bandage needs to be assessed by your veterinarian within 4-6 hours. Call your veterinarian if any swelling is noted.

The bandage must be kept clean and dry. Place a plastic baggy or a boot over the end of the bandage every time your pet goes outside. Remove the plastic covering or boot when indoors.If the bandage gets wet or you notice any bad odor coming from the bandage, it will need to be evaluated within 4-6 hours as serious skin problems may develop.

We strongly advised that you do not modify the bandage in any way. Adding tape or other wrappings can seriously compromise the safety of the bandage/splint. If you are concerned about the security or integrity of the bandage, please return to your veterinarian or veterinary surgeon for re-evaluation and re-application as needed.

Please know that bandages and splints can cause very serious complications. They can be an effective treatment tool for fracture healing and pain control, but careful monitoring and appropriate follow-up must occur. If you have any questions or concerns related to issues outlined above or in general regarding bandage/splint wear, please do not hesitate to call your veterinarian or return for evaluation. Your pet cannot tell you that the bandage hurts or is uncomfortable so you need to be attentive to any change.

Activity Restriction

Confine your pet as directed by your veterinary surgeon. Confinement often includes restricting him or her to one section of the house with carpeted floors, or to a dog kennel. Use baby gates to prevent access to slippery floors and stairs. Do not allow jumping on/off furniture. Do not allow any playing, running, or jumping. For dogs, use a short leash when going outside for bathroom breaks. For cats, confinement is often best achieved with a large dog crate in which food/water, a bed, and a litter pan may be place. A small room may also serve as a confined area, but furniture should be removed to prevent your cat from jumping.

Your pet will feel like fully using the leg before the fracture is sufficiently healed. Please continue the restriction during this time until bone healing has been confirmed with x-rays. Failure to do so may cause serious healing problems.

Assisting Your Pet

Your pet may need assistance to stand and walk in the first few days or weeks following his/her injury. Even if your pet is able to move on his/her own, it is often wise to provide light assistance until he/she is completely stable, especially on slippery surfaces or when going up or down a short flight of stairs. Dogs will often accept help; cats rarely do. Some dogs will fight the assistance and refuse to move. Adjust your efforts as needed to help your pet without creating more difficulties for both of you. Some pets will need to be held up strongly, others will just need light support to prevent slipping or falling to one side.

There are several sling-type products commercially available that are specifically designed to help you help your dog walk during his/her recovery. You may find some of these products online and they are definitely easier to use than homemade slings.

Physical Therapy

When a bone is fractured, many things happen that make a leg function poorly over the fracture healing period. Muscles, nerves and blood vessels are damaged; the result is pain and poor muscle function. If a leg is weak and/or hurts to stand on, an animal won’t use it properly. When a leg is not used for several days to weeks, joints stiffen, muscles get smaller (atrophy), and bone healing is delayed. Physical therapy during fracture healing uses methods aimed at improving comfort and leg use without harming bone healing. Some of the simpler methods can be used at home and more advanced techniques are used by veterinary physical therapists under the guidance of your veterinary surgeon. Careful coordination between your pet’s veterinary surgeon and physical therapist can result in excellent outcomes and an efficient return to normal leg function.

Simpler methods that can be used at home include:

- Cold therapy: In the first week after injury, applying cold packs to the fracture site will reduce inflammation, swelling and pain; this will make your pet more comfortable and allow him/her to use the leg earlier.

- Range of motion therapy: In the first month after injury, flexing and extending the joints of the injured leg will maintain joint health while your pet is not using the leg fully. Initially this range of flexion and extension will be quite small; the goal is to move the joint without creating pain. As healing progresses, more stretching can be applied to reach toward a more normal range of joint flexion and extension.

- Massage therapy: After the initial stage of painful inflammation subsides, you may be instructed to begin massage therapy on the skin and muscles around the injured bone. This therapy will prevent tough scar tissue from developing that will later prevent normal movement of the leg, and it also offers pain relief in the intermediate period of healing.

Bone healing is dependent upon some of the same factors listed in the chart above. Young dog and cat bones heal faster than old dog and cat bones. Bones that have lots of muscle and blood vessel tissues disrupted from the trauma heal slower than bones surrounded by healthy tissues. Bones that are repaired with minimal surgical trauma (no or small surgical incision) heal faster than those with a lot of surgical trauma.

Your veterinary surgeon should be able to tell you what to expect with healing. As a general statement, fractures need a minimum of 4 weeks in young puppies and 8 weeks in adult/older animals to heal sufficiently for your pet to begin to progress to normal activities.

We do not have the luxury of telling our patients to “take it easy” and “stay off of it”, so we must rely on you (the pet owner) to impose these restrictions even when your pet is begging to romp and play. It is a long 2-3 months when the sun is shining and the squirrels are asking to be chased, but catastrophe can happen if the fracture repair is stressed too soon. Ultimately, most fractures will heal well and bones can resume near normal shape and strength. With close attention to your pet and appropriate follow-up care and physical therapy, our broken pets can return to completely normal lives.