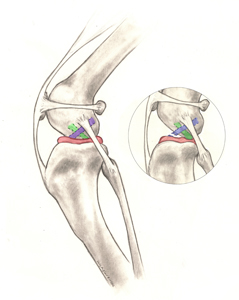

The cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL, see Figure 1.) is one of the most important stabilizers inside the canine knee (stifle) joint, the middle joint in the back leg. In humans the CrCL is called the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). This ligament prevents the knee from moving back and forth excessively.

The meniscus (Figure 1) is a ‘cartilage-like’ structure that sits in between the femur (thigh) and tibia (shin) bones. It serves many important purposes in the joint such as shock absorption, position-sensing, and load-bearing and can be damaged when the CrCL is ruptured.

Rupture of the CrCL is one of the most common reasons for hind limb lameness, pain, and can cause knee arthritis. While the clinical signs associated with cruciate disease vary, the condition often causes rear limb dysfunction and pain.

Most commonly, cruciate disease is caused by a combination of many factors, including aging of the ligament (degeneration), obesity, poor physical condition, genetics, conformation (skeletal shape and configuration), and breed. With CrCLD, ligament rupture is a result of subtle, slow degeneration that has been taking place over a period of time rather than the result of a sudden trauma to an otherwise healthy ligament (which is very rare). Partial tearing of the CrCL is common in dogs and almost always progresses to a full tear over time.

Cranial cruciate ligament disease can affect dogs of all sizes, breeds, and ages, but rarely cats. Certain dog breeds are known to have a higher incidence (Rottweiler, Newfoundland, Staffordshire Terrier, Mastiff, Akita, Saint Bernard, Chesapeake Bay Retriever, and Labrador Retriever) while others are less often affected (Greyhound, Dachshund, Basset Hound, and Old English Sheepdog). A genetic mode of inheritance has been shown for Newfoundlands and Labrador Retrievers.

Poor physical body condition and excessive body weight are risk factors for the development of CrCLD. Both of these factors can be influenced by pet owners. Consistent physical conditioning with regular activity and close monitoring of food intake to maintain a lean body mass is advisable.

Dogs with CrCLD may exhibit any combination of the following signs:

- difficulty rising from a sit

- difficulty in the process of sitting (“positive sit test”)

- trouble jumping into the car

- decreased activity level or unwillingness to play

- lameness (limping) of variable severity, sometimes only noted after long periods of rest

- muscle atrophy (decreased muscle mass in the affected leg)

- decreased range of motion of the knee joint

- a popping / clicking noise (which may indicate a meniscal tear)

- firm swelling on the inside of the shin bone (fibrosis or scar tissue)

- pain

- stiffness

Pain and discomfort are expressed differently in people compared to dogs, so although dogs may not whine, cry out, or hold up their affected limb constantly, the persistence of their lameness is a sign of pain.

Cruciate tears can be diagnosed from hands-on exam alone. Diagnosis is made upon eliciting forward motion of the tibia (cranial drawer sign) or via the presence of tibial thrust. This is easy in acute, complete ruptures, but may be more subtle in chronic or partial tears. Mild sedation to allow muscle relaxation and radiographs to demonstrate arthritic changes and swelling may be necessary to obtain a diagnosis. Radiographs are only required if surgery is performed to allow for surgical planning. However, radiographs may help support the exam findings in difficult cases.

Prior to surgical intervention or administration of anti-inflammatory medications for pain relief, your veterinarian will also likely perform bloodwork or ensure that your pet has had it recently performed. Knowing the overall health of your pet is important before focusing on orthopedic surgery or dispensing certain medications.

Many treatment options are available for cruciate injury. The first major decision is between surgical treatment and non-surgical (also termed conservative or medical) treatment/management. The best option for your pet depends on many factors, including their activity levels, size, age, skeletal conformation, and degree of knee instability.

Surgical treatment is typically the best treatment for cruciate injury since it is the only way to permanently control the instability present in the knee joint. Surgery addresses one of the main issues associated with CrCLD—knee instability and the pain it causes as a consequence of the loss of normal CrCL structural support.

In humans, the cruciate ligament is often replaced. This has not been possible with dogs. However, there are several treatment options.

Osteotomy-based techniques require a bone cut (osteotomy), which changes the forces on the knee joint and prevents instability when walking. Many surgeons prefer these techniques for large, active dogs, while some surgeons prefer these techniques for even small dogs and cats, because of their consistent outcomes in even the most athletic of patients and reduction in the rate of arthritis formation:

-

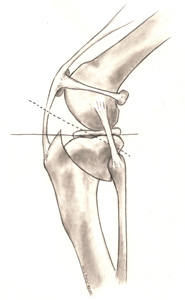

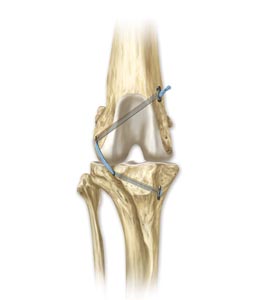

- Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO) involves making a semicircular cut around the top of the shin bone and rotating this to a predetermined location (Figure 2). This renders the knee more stable in the absence of the CrCL. The cut in the bone is stabilized by the use of a bone plate and screws (Figure 3). Once the bone has healed, the bone plate and screws are not needed, but they are rarely removed unless there is an associated problem (irritation, infection). This procedure has consistent outcomes, and the majority of dogs can go back to an active lifestyle after they have healed. The procedure does require time for the bone to heal and requires several weeks of confinement to prevent complications.

- Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA) requires a linear cut along the front of the shin (tibia) bone. The front of the tibia, is moved forward to neutralize forces around the knee. The cut in the bone is stabilized by the use of a specifically designed wedge, bone plate, and screws. Similar to the TPLO, this procedure requires several weeks of confinement while the bone heals.

- CORA-Based Leveling Osteotomy (CBLO) is a newer technique that is similar to the TPLO, but changes where the cut is made on the bone. Similar to the TPLO, a radial cut osteotomy is utilized to level the tibial plateau. This procedure is useful in young animals with open growth plates.

Figure 4. TTA. The front of the tibia is advanced forward until the attachment of the quadriceps is oriented approximately 90 degrees to the tibial plateau

Suture-based techniques involve involve placing suture to mimic what the intact cruciate ligament does in the dog.

- Extra-capsular suture stabilization (also called “Ex-Cap suture,” “lateral fabellar suture stabilization,” and the “fishing line technique”) is a popular technique. In this procedure, heavy suture is placed outside of the joint that mimics the place where the cruciate ligament is. This stabilizes the joint while the body puts scar tissue around the knee to hold things in place. The most common complications after this procedure involve failure of the suture and development of arthritis. While this technique is often less costly, it may not be the best choice for larger and younger patients due to the onset of arthritic changes.

- The Tightrope® utilizes a specifically developed suture and toggle implants that are placed in holes drilled through the thigh (femur) and shin (tibia) bones (Figure 5). This allows more accurate placement of the implant and better “suture” strength compared to the extra-capular suture.

Non-surgical treatment usually involves a combination of pain medications, exercise modification, joint supplements, physical rehabilitation, and possibly braces/orthotics.

-

- Activity restriction and anti-inflammatories – While administration of pain medications to dogs with cruciate disease may improve their comfort, knee pain persists because of continued knee instability. For this reason, strict activity restrictions (e.g., leash-based activities) are typically most effective at reducing pain. Over time, the body may stabilize the knee joint with scar tissue, but the knee is predisposed to reinjury when the patient is active in the future.

- Rehabilitation therapy – Rehabilitation may help strengthen the muscles around the knee joint and can help delay surgery in dogs with partial cruciate tears.

- Custom knee bracing/orthotics – Custom knee bracing is relatively new to canine orthopedics and there is little disease on outcomes. Braces can be pricey and have potential complications such as sores, continued pain, and patient intolerance.

- Intra-articular injections – There are various options available for injectable therapies that can be used to attempt to address cruciate ligament injury.Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or autologous conditioned plasma (ACP) is a specialized blood product made by concentrating a patient’s own platelets. The concentrated platelets can be used to supplement the patient’s own growth factors to improve the recruitment of cells to an injury site.

Postoperative care at home is critical. Activity must be restricted for several weeks after surgery to ensure that there are no complications with implants or healing after surgery for cruciate disease. Complications can include:

- Infection

- Implant breakage (stretching of sutures, breakable of plates or screws)

- Bone fracture

- Meniscal tear

- Continued lameness

- Arthritis development or progression

- Muscle loss

Studies show that physical rehabilitation can speed up a dog’s recovery and improve final outcomes regardless of the chosen surgical technique. This rehabilitation should start immediately after surgery and usually includes a regime of passive range of motion, balance exercises, controlled walks on a leash, and so forth. Additional details should be discussed with a board-certified surgeon and/or a primary care veterinarian.

The long-term prognosis for animals undergoing surgical repair of CCLD is good, with reports of significant improvement in 85-90% of the cases. While arthritis can progress over the years regardless of treatment type, it’s expected to be at a slower rate when surgery is performed compared to medical management. Since this is likely a degenerative process in dogs, it’s important to note that up to 50% of animals diagnosed with cruciate disease in one knee will develop the same condition in the other knee, usually within the first 12-18 months after diagnosis.

- 40-60% of dogs that have CrCLD in one knee will, at some future time, develop a similar problem in the other knee.