Gastrointestinal (GI) foreign bodies occur when pets consume items that are non-digestible and will not readily pass through their stomach or intestines. These items may be toys (Figure 1), leashes, clothing, sticks, or any other item that fails to pass, including human food products such as bones or trash. When these items become lodged in the GI tract, they can cause the animal to become very sick. The problems that are caused vary with:

- how long the foreign body has been present.

- the location of the foreign body.

- how badly the foreign material closes off the opening of the GI tract.

- what the material is made of. Some ingested items, such as older pennies or lead material, can cause systemic toxicities while others may cause regional damage to the intestinal tract itself due to compression or obstruction.

Gastrointestinal foreign bodies, especially strings, can sometimes cause holes in the tissue (or perforation). This causes spillage of intestinal contents into the abdomen. This condition quickly leads to life-threatening inflammation of the abdominal lining (peritonitis) and allows bacterial proliferation and contamination (sepsis). While some small foreign bodies will pass, many will become lodged along the gastrointestinal tract and cause discomfort and make your pet sick. Some foreign bodies located in the stomach may be retrieved with the use of an endoscope; however, most require surgical abdominal exploration and removal. Occasionally, foreign bodies will become lodged in the esophagus at the base of the heart or at the diaphragm, which may require thoracic (chest) surgery.

Clinical signs can vary significantly with the degree of obstruction, location, duration, and type of foreign body. Commonly noted signs include:

- vomiting

- anorexia (loss of appetite)

- abdominal pain

- dehydration

- diarrhea (with or without presence of blood)

- abdominal fluid

In cases of linear foreign bodies, a string may be observed wrapped around the base of the tongue (Figure 1) or coming out of the anus.

The symptoms of a foreign body or intestinal obstruction can cause dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. This can cause the pet to feel systemically ill as well. Additionally, if the foreign body has perforated the GI tract and entered the chest or abdominal cavities, the animal may be profoundly ill and in critical condition. These may cause peritonitis, sepsis, and death.

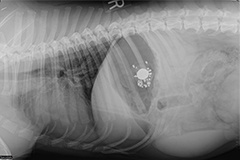

Your primary care veterinarian will likely recommend initial blood work that includes a complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry, and a urinalysis. These combined will help to rule out other causes for your pet’s symptoms. Abdominal, and occasionally thoracic, radiographs are regularly performed (Figures 2 and 3). Positive contrast radiographs (using barium to highlight the inside of the stomach and intestines) may be performed when routine radiographs fail to show the cause for the clinical signs. Abdominal ultrasound can be very helpful in identifying gastrointestinal foreign bodies. In some cases, advanced imaging such as a CT scan may be needed.

Surgery is not always required with gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Occasionally, the item ingested is small and smooth enough to pass through the gastrointestinal tract without causing damage or becoming lodged. Your veterinarian may recommend hospitalization for intravenous fluids and monitoring to help the item pass in this case. Additionally, some foreign bodies may become lodged in the upper gastrointestinal tract (mouth, esophagus, and stomach) and may be retrieved by making the pet vomit or with the use of a flexible endoscope (tube with a camera). If conservative management and endoscopy fail to provide relief, if the foreign body is not moving on x-rays, if the obstruction is getting worse, or if there is evidence of a linear foreign body, surgical exploration is warranted.

Esophageal foreign bodies require thoracic (chest) surgery to gain access for removal. Most gastrointestinal foreign bodies become lodged within the stomach or intestines and require a gastrotomy (opening the stomach) or enterotomy (opening the intestine). Once the item has been removed, the gastrointestinal tract is closed. If the intestine has become severely damaged, the section is removed and the healthy ends are reattached (an intestinal resection and anastomosis). The decision of which procedure to perform is determined by the surgeon when all the intestines and other abdominal organs have been evaluated. Most times, this decision is only made in surgery when the surgeon can visually assess the damage to the intestine and surrounding tissues.

Animals are kept on intravenous fluids, and their vital signs are monitored for 12-24 hours after abdominal surgery. In some cases, a small tube is placed through a nostril into the stomach to help remove built up fluid and gas. In cases with severe intestinal damage, intravenous antibiotics may be given. Food is offered when the pet recovers. Early return to oral nutrition is important to help the gut heal after surgery. Electrolytes and other blood values may be checked periodically during recovery. When pets are eating on their own and able to take oral medications, they can be discharged.

Complications of intestinal surgery can include reduced motility of the GI tract (ileus), narrowing of the intestine where surgery was performed (stenosis or strictures), short bowel syndrome, or leakage into the abdomen. The most serious complication of this procedure is intestinal leakage. Abnormal healing, damaged tissue, or breakdown of the suture material can all be factors that cause post-operative leakage. Leakage can happen in the first 5 days after surgery. Symptoms of leakage can include lethargy, increased inappetence, vomiting, fever, drainage from the incision, or a distended abdomen. If these signs are seen after GI tract surgery, your pet should be re-evaluated as soon as possible. Animals with leakage usually require revision surgery and may need extended hospitalization.

Animals that have large sections of intestine removed (>75%) are at risk for a condition known as short bowel syndrome. When large amounts of the intestine are removed, there is reduced surface area for digestion to occur. This can result in maldigestion and malabsorption which causes persistent watery or oily appearing diarrhea and weight loss. There are treatments that can be given and some animals’ intestines may adapt over time, but it is important to work with your veterinarian to ensure your pet is receiving proper nutrition if they have this condition.

Prognosis following GI foreign body surgery is usually quite good. It is important to try to prevent your pet from ingesting any more foreign material. Repeated abdominal surgeries become much riskier if adhesions form. You can try keeping your pet in a kennel or room without foreign objects when not supervised. Animals that repeatedly ingest foreign material may need to wear a basket muzzle to prevent further ingestion.