When puppies or kittens are born, they have several open growth plates, or physes, within their bones which allow the bones to increase in length and develop their appropriate shape, including various prominences where ligaments and tendons attach. The timings at which these growth plates should close varies depending upon the individual growth plate and size of the patient concerned, however, there are fairly well-defined times at which these should close. Until this closure occurs however, these growth plates remain a weak point within the bone, more liable to fracture than the remainder.

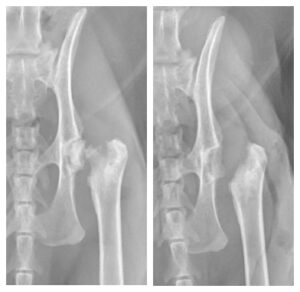

Femoral capital physeal fractures (FCPF) are fractures that occur through the growth plate located at the femoral head (Figure 1): the “ball” of the ball and socket joint of the hip. While both dogs and cats can develop fractures in this area, it more common in the feline population. While the majority of fractures are accompanied by a history of some sort of traumatic event, cats, and a small population of dogs, may develop this particular fracture without any such history, a condition known as a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE); these fractures are thought to occur secondary to abnormal development of the growth plate.

In cases where an FCPF is sustained secondary to trauma, there is no reported predisposition. However, with SCFE, gender, age, and breed play a role with males, cats over 1 year of age, Maine Coons, British Shorthairs, Bengals, and Siamese breeds being at higher risk of development of this atraumatic injury.

Your cat or dog may present with a sudden onset, usually non-weight bearing, lameness of a hindlimb, especially in cases where a traumatic event has been witnessed or suspected. The majority of SCFE cases also present in this fashion, however a chronic, weight-bearing lameness of a hindlimb is also possible, or your cat may simply appear less active or willing to jump.

Remember that cats tend to be good at hiding illnesses, and this includes orthopedic disease, so the true lameness that we often observe in dogs may not be as obvious in cats. More subtle signs of hindlimb lameness or orthopedic pain in cats include: decreased activity, changes to grooming behavior (under or over grooming), inability or hesitancy to jump up, not being able to jump as high as previously, hesitancy or being unable to go upstairs, difficulty with rising from a sitting or lying position, decreased play drive, manifesting a pain response when being touched around the hind end and avoiding interactions with you, other people, or other pets. It is recommended to have your cat evaluated by your primary care or emergency veterinarian if you are noting evidence of lameness or altered activity levels.

When presenting your pet for an initial appointment for concerns of lameness or pain, your primary care or emergency veterinarian will likely recommend starting off with radiographs (colloquially termed x-rays). Luckily, FCPFs can usually be diagnosed using this technique in isolation, but occasionally, for subtle cases, additional imaging in the form of a Computed Tomography (CT) scan may be required.

Multiple injuries associated with SCFE are rare, so if there is no history of trauma, additional imaging is likely not necessary. However, in cases of FCPF where trauma was observed or suspected, more testing may be indicated to look for any other injuries your pet may have sustained. A pet being hit by a car for example, may have sustained additional fractures or soft tissue injuries (i.e. bruised lungs, organ laceration, etc.) which additional radiographs or more advanced imaging modalities can diagnose. Bloodwork to evaluate the overall health of your pet will likely be recommended by your veterinarian in cases of trauma, prior to administration of medications and in pets undergoing anesthesia for surgical repair.

Fracture Repair with Pins or Screws:

Primary fracture repair, where the fracture is surgically put back together and secured in place using orthopedic implants (either pins or screws), can be performed in most cases by an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon (Figure 2).

In some cases of SCFE, due to chronicity of the fracture and/or the presence of unhealthy bone surrounding the fracture site, primary repair of these fractures may not be possible, recommended, or may be associated with a higher risk of complications.

Salvage Procedures:

Salvage procedures are surgical options chosen when alternatives are unable to be performed in a given case. This could be secondary to external factors, such as finances, or internal factors, like poor bone quality or a perceived increased risk of complications with a pet that has other concurrent conditions, such as hip dysplasia for example.

Femoral Head and Neck Ostectomy (FHO):

An FHO procedure involves surgical excision of the femoral head and neck (the top portion of the thigh bone that connects it to the hip joint) (Figure 3). This removes the site of the fracture and prevents bone-on-bone contact from the remaining cut surface of the thigh bone against the pelvis. As a portion of the hip joint is no longer present, this creates a false joint where surrounding muscles and other soft tissues hold the site together and allow movement. Because this is no longer a true joint however, it will not have a normal range of motion compared to an unaffected hip and the operated limb will be shorter than the limb on the other side. Physical rehabilitation with a veterinary specialist is recommended after an FHO procedure to retain the greatest range of motion possible post-operatively.

Total Hip Replacement (THR):

THR procedures in dogs and cats are similar to those performed in humans. The procedure involves replacing the femoral head and neck with metal implants, while replacing the acetabulum (the “socket” of the ball and socket joint) with a metal cup containing a plastic inner lining (Figure 4).

As the structure of the hip joint is maintained through the placement of these implants, the hip will function as a normal joint and a normal range of motion should be maintained in addition to normal limb length.

Post-operatively, reevaluation with radiographs will need to be performed with a veterinary surgeon at various time points throughout the life of your pet. This is to ensure that the implants are continuing to function appropriately and to help mitigate potential risks by identifying problems and where necessary, intervening early, which can help avoid catastrophic complications.

Non-Surgical Management:

While not the recommended option for FCPFs due to high rates of persistent pain, mobility issues, chronic lameness, and progressive osteoarthritis formation, non-surgical management can be considered as a last resort in select cases. Treatment with pain medications, sedatives, and strict cage rest would be recommended for several weeks with recheck evaluations to assess for healing at the level of the fracture site. The fracture would be unlikely to align perfectly in its original position with this treatment, and unfortunately, in many cases, fracture healing fails to occur. Due to this, persistent pain and complications are more commonly encountered with non-surgical management of this condition.

Post-operative aftercare and outcomes are dependent upon the treatment option chosen. It is important to note that you should have in-depth conversations with your veterinary surgeon about the recommended and potential treatment options available for your pet, as the descriptions detailed here are generalized and do not give specific information to your dog or cat’s potentially unique situation.

With primary repair of your pet’s fracture, cage rest will be recommended for approximately 6-8 weeks, until the fracture has healed. Rechecks with a veterinary surgeon will be necessary to check for radiographic evidence of healing prior to allowing a return to normal activity. It is possible that implants can fail, so strict adherence to post-operative instructions is of the utmost importance to avoid such complications. In the absence of complications, this treatment option is associated with good-to-excellent clinical outcomes as the function of the hip joint is maintained.

In most cases, the FHO procedure is reported to have a good prognosis, however, this is somewhat variable and dependent upon physical rehabilitation for optimal outcomes to be achieved. It should be remembered that this “false joint” no longer has the same characteristics as a normal hip joint and therefore your pet will have a reduced range of motion of that hip. Additionally, a mild-to-moderate lameness may be associated with this abnormal anatomy and reduced muscling on the operated limb is not uncommon. Following this procedure, while unrestricted activity would not be allowed, after the first two weeks, pets undergoing FHO are typically permitted more activity during their recovery period when compared to other treatment options, as long as this is their only injury. Since no implants are used or left in the body with this technique, a true “failure” is not possible, however outcome can still be variable depending upon the range of motion, muscling and limb length achieved following the procedure.

Pets undergoing THR have an excellent prognosis with regard to both comfort and mobility. As the joint itself is replaced, this allows normal hip range of motion, limb length and muscling to be maintained. Intense post-operative care is required – usually 8-12 weeks of strict rest with avoidance of slippery floors and potentially support while walking (such as the use of slings) for the first few weeks. The implants used to replace the joint, similar to a surgical repair of the fracture, also have the potential for complications, such as dislocation of the new hip joint, fracture of the bone surrounding the implant, and implant-associated infection. Therefore, as above, strict adherence to post-operative recommendations is warranted to mitigate these risks.

Because SCFE in cats is suspected to be secondary to abnormal development of the femoral head growth plate, it is also possible that your cat may sustain another fracture on the other hindlimb. Continued monitoring for any lameness episodes or changes in activity is warranted, especially in cats noted to be at higher risk of sustaining these fractures.