In adult dogs and cats, the heart has two sides that are not connected directly. Deoxygenated blood comes into the right side of the heart from the rest of the body. The right side of the heart pumps blood into the lungs through the pulmonary artery. Once in the lungs, it picks up oxygen. Then, oxygenated blood is directed to the left side of the heart via major blood vessels called the pulmonary veins. From the left side of the heart, oxygenated blood is pumped to all parts of the body through a large blood vessel called the aorta.

It doesn’t work this way when the fetus is in the womb, as they are not developed enough to breathe in oxygen. A developing fetus relies on the umbilical blood vessels and circulation to pick up oxygen from the mother to deliver it to the growing body. The lungs are still developing in the fetus and are filled with fluid. The blood vessels in the lungs are underdeveloped, as there is no reason to send blood to the lungs. The blood vessels in the lungs only bring nutrients to the developing lungs.

Thus, in a developing fetus, a short bypass blood vessel called the ductus arteriosus shunts the majority of blood from the right side of the heart, bypassing the lungs, directly into the aorta and to the rest of the developing body. Only a small volume of blood that has nutrients is taken into the developing lungs.

When the puppy or kitten is born, the first breath of air taken fills the lungs with oxygen and inflates them. Blood can now circulate through the lungs and pick up oxygen, and through the heart, it delivers oxygen to the rest of the body. Consequently, the pressure in the lungs’ circulation drops significantly, and blood now prefers to flow out of the lungs. Therefore, the bypass blood vessel (Ductus arteriosus) is no longer needed or used. Oxygen and other hormones cause the ductus arteriosus to close almost immediately. When this blood vessel closes, it becomes scar tissue. Ductus arteriosus usually closes within the first three days (maximum of 7-10 days) after birth.

However, sometimes the ductus arteriosus (bypass blood vessel) fails to close after birth and remains patent or functional. This congenital abnormality, in which the ductus arteriosus remains patent, is known as the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Consequently, blood is shunted from the aorta into the lungs as the pressure in the aorta is higher than the pressure in the lungs. Some blood still flows through the aorta to the rest of the body, but this flow is significantly reduced due to shunting. As a result, oxygenated blood mixes with deoxygenated blood, and more blood flows into the lungs and subsequently into the left side of the heart. This type of flow is called a left-to-right shunt. Eventually, there is persistent overloading of the left side of the heart, causing left-sided heart failure if left untreated.

A left-to-right shunting PDA manifests as a continuous murmur that can be auscultated with a stethoscope on the left side of the chest. Pets suffering from this condition may exhibit other signs, including difficulty breathing, exercise intolerance, fatigue, weakness, and collapse. These signs may manifest as shortness of breath, difficulty walking or participating in regular activities, failure to thrive, or exercise-induced collapses. In severe cases, it can cause fluid buildup in the lungs (pulmonary edema), which is commonly referred to as left-sided congestive heart failure (CHF). The probability of developing CHF with a left-to-right-sided shunt depends on the size of the PDA and how much blood is shunted back into the lungs. Suppose you notice any of the above signs in your pet, or suspect your pet may be in heart failure. In that case, you should take your pet to a veterinary emergency hospital or to your veterinarian on an emergency basis to control the heart failure with medications before surgery or occlusion of the PDA is pursued.

Your primary care veterinarian can typically diagnose a left-to-right shunting Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA) by auscultating the heart with a stethoscope. A distinctive, continuous, loud murmur, reminiscent of a washing machine, is heard on the left side of the chest.

Certain dog breeds are at an increased risk for developing a PDA, including the Maltese, Pomeranian, Shetland Sheepdog, English Cocker Spaniel, American Cocker Spaniel, Keeshond, Bichon Frise, German Shepherd, Border Collie, Irish Setter, Kerry Blue Terrier, Labrador Retriever, Newfoundland, Miniature and Toy Poodle, Chihuahua, and Yorkshire Terrier. Additionally, PDA occurs more frequently in female dogs.

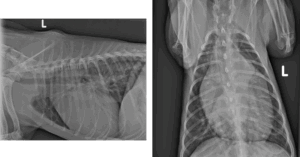

To further evaluate the condition, your veterinarian may suggest performing chest radiographs (Figure 1) to check for fluid buildup in the lungs, which can indicate heart failure resulting from excess blood shunting into the lungs. To confirm the diagnosis, your veterinarian may refer you and your pet to an American Board-Certified veterinary cardiologist (ACVIM – Cardiology) for an echocardiogram (a heart scan). This procedure enables direct visualization of the PDA, measurement of the heart chambers, and assessment of the PDA’s size and function. Furthermore, an echocardiogram can identify other congenital heart defects that may not be immediately apparent, as it is not uncommon for puppies or kittens to have multiple congenital abnormalities. This comprehensive information enables the veterinary cardiologist to recommend the most effective treatment for your pet with PDA.

Once diagnosed, it is advisable not to delay treatment until the pet reaches adulthood or becomes seriously ill. Without intervention, approximately two-thirds of affected puppies may not survive past their first year. Moreover, the older the pet is at the time of correction, the greater the risk of complications due to the pet’s deteriorating health and the increased fragility of the Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA).

There are multiple ways to treat the more common left-to-right PDA. If the PDA is small, a veterinary cardiologist might elect to do nothing because it will not cause any problems over the life of your pet. If a PDA is large enough to cause significant shunting and problems, then several options exist to close it. For most pets, endovascular occlusion (a minimally invasive option) is commonly recommended as the treatment of choice. However, if your pet is a toy breed dog or cat, or smaller than five pounds in size. In such cases, the minimally invasive option may not be suitable due to the pet’s small body size, a large PDA, or small blood vessels. On such occasions, surgery would be more ideal for occluding the PDA. If surgery is an option and is pursued, please check with your veterinarian for referral with an American Board-Certified Veterinary Surgeon (ACVS – Small Animal). Because the decision-making process can be complex and depends on several factors for choosing the right treatment option, it is highly recommended that you consult with both a veterinary cardiologist and a veterinary surgeon to determine the best treatment option for your pet.

Endovascular occlusion (minimally invasive option)

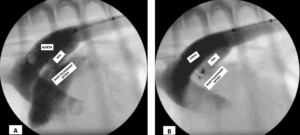

For pets with PDA, the most common option today is to deploy a device via the aorta into the PDA to permanently occlude it. Initially, small coils were used, and they are occasionally still used. Currently, a specific device called the Amplatz Canine Ductal Occluder (ACDO) is used to occlude the pet’s PDA (Figure 2).

The ACDO device resembles a two-sided umbrella that is opened inside the PDA, with a portion of the device on each side of the PDA opening. The size of this device is typically selected by the veterinary cardiologist based on the size of your pet’s PDA, ensuring it fits snugly within the PDA and causes almost immediate clotting, thereby occluding the shunting of blood (Figure 3).

Complication rates with occlusion devices are similar to or lower than those with surgery because of their minimally invasive nature. Only a catheter is introduced through the femoral artery of your pet to deploy the device into the PDA. However, in some cases, if the PDA size is enormous, in toy-breed dogs, cats, or dogs weighing less than five pounds, this option may not be suitable and may require surgery.

Surgical ligation

Direct ligation of the PDA is the traditional method to close the PDA. The chest is opened, and a suture is used to tie off the PDA. This procedure is not something most veterinarians are likely to attempt or feel comfortable with, as this is a highly delicate surgery and usually requires a Veterinary Surgeon. Discuss with your veterinarian whether a referral to a veterinary surgeon is in your pet’s best interest.

The complication rate is less than 5 percent, with fewer than 2 percent requiring a second procedure to completely close the PDA. This does require open chest surgery. In cats and toy breed dogs or dogs less than five pounds, surgery is usually the method of choice for closing the PDA due to their smaller body size and smaller blood vessels.

Reverse PDA

Surgery or occlusion of the PDA is not an option for right-to-left PDA, as these cannot be corrected. The only treatments are directed at secondary complications. With the right-to-left shunting PDA, the pet’s body has an oxygen debt. In response to this, the pet’s body produces more red blood cells, resulting in a condition called polycythemia. With more red blood cells in the pet’s blood, the blood becomes thicker and more viscous, making it difficult to flow. This can lead to clot formations, and in some pets, it can cause seizures. Therefore, the treatment is usually aimed at decreasing the number of red blood cells, either by removing some blood and replacing it with saline or by using certain medications that interfere with red cell production. Suppose pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in lung blood vessels) is also diagnosed via the echocardiogram (heart scan) by the veterinary cardiologist. In that case, it is managed with medications. Unfortunately, these are palliative measures as pets will never be normal and will likely succumb to the disease at around 5-6 years of age.

For pets undergoing surgery, an incision will be made on the left side of the chest. They will be required to wear an Elizabethan collar for 10-14 days to prevent them from licking or chewing on their incision and to prevent infection at the incision site. Your pet should also be on a restricted activity regimen to prevent them from injuring themselves.

For pets undergoing endovascular occlusion, the incision is small and made in the inner thigh area to access the femoral artery. Veterinary cardiologists may recommend that your pet be on strict rest and have a restricted activity level for up to 4 weeks to prevent inadvertent dislodging of the device.

Regardless of the method of PDA occlusion, your pet will require a 2-week recheck to ensure the incision(s) are healing well, followed by a recheck in 4 weeks with the veterinary cardiologist for a recheck echocardiogram to confirm that the PDA has been completely occluded.

If the occlusion of the left-to-right shunting PDA is successful, your pet should be able to lead an otherwise normal life. This is one congenital heart defect that is essentially curable, even if diagnosed and treated later in life, provided the pet lives that long and if they don’t develop the right-to-left shunting PDA. The sooner it is treated, the better. In most cases, cardiologists and surgeons will recommend and correct the PDA within the first 6 months to 12 months of a pet’s life. Indeed, the longer you wait to occlude a PDA, the more challenging it becomes, as pets can develop other secondary complications and the PDA can become more fragile, tearing more easily. If your pet has irreversible damage before occlusion, it may need medications for the rest of its life.