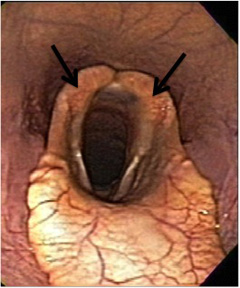

Laryngeal hemiplegia is a disease that affects the upper airway in horses. It causes a decrease in airflow to the lungs and can cause exercise intolerance. Horses with the disease are called “roarers” because they make a characteristic respiratory noise that sounds like “roaring” when exercised. The larynx (similar to the voice box or Adam’s apple in humans) is the structure that connects the nasal passage to the trachea (also known as the windpipe). It consists of a group of cartilages that allow air to pass into the trachea and protect the airway during swallowing. Laryngeal hemiplegia is caused by paralysis of one or both of these cartilages (called the arytenoid cartilage; Figure 1), due to lack of innervation causing atrophy to the muscle that moves the arytenoid cartilage. The left arytenoid cartilage is the most common side affected (up to 95%). In a normal horse, the arytenoids (commonly called flappers) allow maximal airflow into the trachea during abduction (the outward movement of the arytenoid cartilages to open the entrance into the trachea). Horses with laryngeal hemiplegia have paralysis of the arytenoid cartilage, which prevents them from abducting or opening their throat during inspiration. This leads to decreased airflow into the lungs due to obstruction from the paralyzed cartilage resulting in respiratory noise and exercise intolerance.

Laryngeal hemiplegia is most commonly reported in the racing Thoroughbreds but it also occurs in other performance horses including Warmbloods, Draft horses, Standardbreds, and Quarter Horses. It is commonly seen in taller male horses, usually greater than 15 hands. While the disease is not life-threatening, there are several surgical options available to treat your horse if they are experiencing clinical signs and most of them have a good prognosis for improving your horse’s performance.

- Usually seen in horses between 3–7 years old

- Exercise intolerance that has gotten worse over weeks to months

- Classic “whistling” or “roaring” noise heard during exercise (usually while cantering or higher activity)

- Sound of the horse’s whinny may change

- Gasping for breath after exercise

- Veterinarians may note muscle atrophy (or shrinking) at the throat latch area

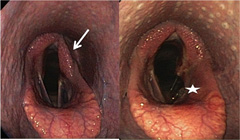

Laryngeal hemiplegia is graded on a scale of 1–4, with 4 being complete paralysis of the cartilage. Standing endoscopy (or “scoping”; Figure 2) can diagnose cases that are grade 3–4 and some cases that are grade 2. High-speed treadmill endoscopy (Figure 3) or over ground dynamic respiratory examination may be necessary to diagnose cases that are questionable on standing endoscopy and can be used to ensure that no other concurrent upper airway problems are contributing to the exercise intolerance or respiratory noise. Additionally, laryngeal ultrasound can be used to evaluate the density of laryngeal muscle fibers to determine if they are correctly innervated.

Treatment recommendations vary depending on the severity/grade, the breed, the age, and the use of your horse. There are 4 treatment options, as described below: prosthetic laryngoplasty (a “tie-back surgery”), ventriculectomy +/- cordectomy, arytenoidectomy, and neuromuscular pedicle graft.

- Prosthetic Laryngoplasty: This is the most common treatment and can be performed with your horse under general anesthesia or standing while sedated. The paralyzed cartilage is “tied back” into an open/abducted position through an incision in the throat latch area. The suture acts as a “prosthetic” for the paralyzed muscle.

- Ventriculectomy/Cordectomy: The ventricle and the vocal cord (located under the arytenoid cartilage) are removed to widen the airway. This is performed alone or along with a prosthetic laryngoplasty (Figure 4). This procedure alone can improve performance and decrease respiratory noise in draft breeds or in show horses that do not need to perform at high rates of speed. It is done under anesthesia through an incision under the jaw into the airway (known as a laryngotomy) or by using a laser passed through an endoscope (or “scope”) up the nostril. Laryngotomy incisions are often left open to heal on their own. Laser techniques can be performed with your horse awake and standing. No incision is necessary with the laser technique since the endoscope and laser are passed up the nose to the larynx. The standing laser technique is ideal for draft breeds that may have difficulty recovering from general anesthesia.

- Arytenoidectomy: The removal of the paralyzed arytenoid cartilage which acts to enlarge the opening to the trachea. This procedure is ideal for horses with a failed tie-back surgery or with an infected arytenoid cartilage. The procedure requires general anesthesia and is done through an incision into the throat (called a laryngotomy; see Ventriculectomy/Cordectomy). There is a potential increased risk of complications and decreased prognosis for returning to the previous level of competition vs. prosthetic laryngoplasty.

- Neuromuscular Pedicle Graft: Surgery that re-innervates the muscles that control abduction/opening of the arytenoid cartilage. A nerve (first cervical nerve) is taken from one of the neck muscles and a branch of that nerve is placed in the muscle that innervates the arytenoid cartilage. Young horses with grade 3 hemiplegia are considered good candidates; grade 3 horses will respond faster to re-innervation than grade 4 horses. Re-innervation takes six to 12 months for return to function. Horses that have had a previous tieback sustain damage to the nerve used in this procedure; therefore, they are not candidates for this surgery.

Postoperative care varies depending on the surgery performed. Antibiotics, anti-inflammatories and throat spray medications are given after surgery in most cases. Skin sutures/staples may need to be removed if an incision was made. Stall rest and time to return to work will vary depending on your surgeon’s preference, the surgery performed, and the grade of laryngeal hemiplegia. Recheck evaluations may be required by your surgeon depending on the procedure performed.

Prosthetic Laryngoplasty:

Postoperative rest after a tieback usually includes 30 days of stall rest with hand-walking/grazing followed by small paddock turnout or light exercise for 30 days. Gradual return to exercise is usually allowed at 45–60 days after surgery. It is very important to prevent a horse that has had a tieback from exercising until advised by your surgeon, because this can cause increased movement of the suture and could increase the risk of tieback failure.

Ventriculectomy/cordectomy/arytenoidectomy:

Horses that have laryngotomy incisions will require twice daily cleaning of the surgical site. They will also require stall rest with hand walking or small paddock turnout until their surgical site has completely healed, typically around 30 days.

Neuromuscular pedicle graft: Postoperative stall rest is also required for horses after a neuromuscular pedicle graft surgery. Recommendations usually include stall rest for 2–3 weeks followed by small paddock turnout for 12 weeks. Gradual return to training can resume after that.

Complications from surgical procedures include:

Prosthetic Laryngoplasty:

Complications occur in 9 to 47% of horses, including: coughing, aspiration of food or dirt particles into the trachea causing pneumonia, incisional infection or dehiscence, seroma (fluid accumulation under the incision), infection of the suture, breakage of the suture and failure to maintain abduction of the cartilage. Coughing is the most common complication and is often seen immediately following surgery; however, only 5 to 10% of horses will remain chronic coughers. If the suture fails (due to infection, breakage or pulling through the cartilage) a second tieback can be performed; however, success rates decrease and chance of subsequent failure increases.

Ventriculectomy/cordectomy:

Complications from this procedure are rare and the laryngotomy site usually heals with minimal problems. Rarely granulomas (excessive scar tissue) may form at the site of ventricle/vocal cord removal, but this can be managed with anti-inflammatories and/or surgical or laser removal.

Arytenoidectomy:

Complications may include coughing, difficulty swallowing, and aspiration pneumonia.

Neuromuscular pedicle graft:

Complications are minimal and may include seroma formation, infection, and failure of the muscle to reinnervate.

Prognosis depends on your horse’s required level of performance and surgical treatment performed. Overall success rates range from 50-90%; racehorses and those with a higher demand for airflow have slightly lower success rates, while show horses, draft horses, and pleasure horses tend to have higher success rates because the overall demand on the airway is lower as compared to a racehorse. Consult with an ACVS board-certified equine surgeon to determine the best treatment plan for your horse.